Autistic Recognition - Face Blindness #2 [transcript]

- Quinn Dexter

- May 15, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: May 16, 2023

Like many autistic people, I don't recognise faces well, but I can often identify people before they even enter the room...

This article is based on the script of the video of the same name uploaded in February 2022.

You can watch the video by clicking on any of the images in the body of text.

Hi. I’m Quinn and I’m autistic.

Welcome to Autistamatic.

Last week I talked about prosopagnosia or face blindness.

It’s not something that’s unique to autistic people but it is something that’s observed in a lot of autistic lives and like pretty much anything you could mention, our autistic experience is uniquely shaped by our differences to the neurotypical average. You only need look at the comments on last week’s video to see how common autistic face-blindness is, and how much it impacts on our lives.

I’m terrible at recognising faces unless I know someone REALLY well and even then my visual recognition can come a cropper all too often. On the other hand I’ve many a time found myself on the wrong end of someone’s wrath for recognising them when they didn’t want to be spotted or for knowing who’s about to come into a room or who’s in the room next door. I’m not alone in that and I’d like to talk about the ways I and many other autists DO recognise people when our skills with faces just don’t cut it.

On a chilly February night in 1981 an excited 10 year old sat waiting for the next episode of The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. I was a huge fan after listening to the LPs condensed from the original radio series over and again on my cassette player and reading the wonderful book adaptations. It’s still one of my all time favourite pieces of fiction.

It was episode 5, set in The Restaurant at the End of The Universe – a unique dining experience that sealed it’s patrons in a stasis bubble that insulated them from time so they could witness the ultimate, final destruction of the universe as they ate their gourmet meals. We were introduced to the dish of the day, a one off character played by an actor wearing heavy latex prosthetics and make up to look something like a man sized pig with horns.

Seconds after he’d spoken a few words I looked at my mum and said

“It’s Tristan”.

She frowned at me quizzically.

“What do you mean?”

“It’s Tristan” I continued, “from All Creatures Great and Small”

“Where – I can’t see him!”

“Behind Arthur – the Dish of the Day – the pig thing. It’s Tristan from All Creatures Great and Small!”

My mother gave me one of her looks.

It was a look that spoke volumes.

It said “I’m not going to engage with this nonsense”.

It told me she didn’t believe me but that she didn’t want to face the consequences of saying so. It was a look I was very accustomed to.

6 weeks later the actor who played Tristan in All Creatures Great and Small, Peter Davison, was all over the papers after his brief appearance in the final moments of the Doctor Who story “Logopolis”. He was to be the next Doctor Who, replacing fan favourite Tom Baker who had played the role for the last 7 years and was MY Doctor. Doctor Who Monthly ran a profile on Davison with a photo from The Hitchhikers’ Guide showing him in full Dish of The Day get-up.

I ran to my mum to show her but she wasn’t interested. She didn’t even remember doubting me and after listening to me tell the story told me that if it actually HAD happened, then I must have known it was Davison beforehand.

I hadn’t though.

I had no idea before the show was broadcast that he would even be in it.

“All Creatures Great and Small” had been staple viewing in our household for several years and his character, Tristan, the keen and enthusiastic, well spoken younger brother of Yorkshire vet Siegfried Farnon and colleague of the writer James Herriott sounded nothing like the languorous alien beast with a pronounced westcountry accent in the guide, so 10 year old me figured it couldn’t be his voice I’d recognised, and it certainly couldn’t be his face or his body movements under kilos of silicone and foam rubber.

It was a mystery.

Fast forward a couple of decades and I’m waiting for the coffee machine at work whilst a couple of my colleagues were getting in a round for the rest of their department and gossiping about their boss Tracy.

I waited patiently for a few moments then cleared my throat... “Excuse me…”

One of them swung round and snapped “Just wait OK – we’ll only be a couple of minutes!”

“No…” I whispered back. “You’d better change the subject. Tracy’ll be coming down those stairs any second”.

She looked nervously over at the staircase and, sure enough, Tracy appeared on the landing where the stairs came round the corner. My colleagues fell silent then smiled at her.

“Hi Tracy, we’ve got you your latte OK!”

“Ooh smashing, thanks” Tracy called as she hurried to the ladies room.

As the door closed behind her I heard a hiss behind me.

“Why did you wait around and say nothing if you knew she was coming down. Were you trying to drop us in it or something?”

“No” I protested. “I wouldn’t have told you at all if I was causing trouble. I just didn’t realise until then.”

“Pull the other one” she snapped.

“You must have seen her before you came down. Guess you get your kicks out of watching people panic.”

Again I was put on the back foot for recognising someone when other people couldn’t and I didn’t know how.

Similar things happened so often I’d frequently wish I’d never opened my mouth, but I always fell into the trap of trying to help, even when it backfired on me. Now after many years of introspection and experiment I finally know. It’s a by-product of my personal Autistic Triad.

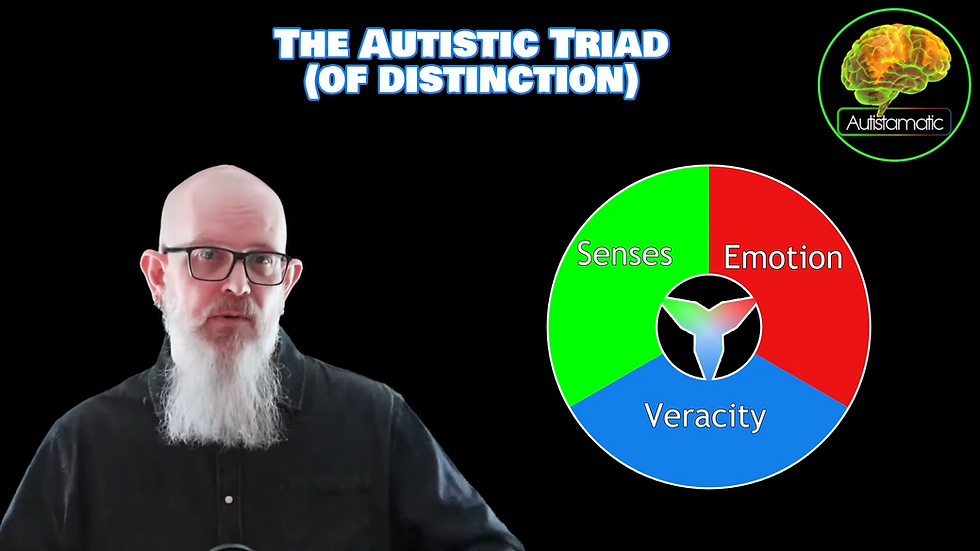

The autistic triad of Senses, Emotions and Veracity impacts on everything that makes us different as autistic people including the way we recognise other people. Not every autist has the same difficulty recognising faces that I do, but even so, it seems that even those of us who CAN spot a familiar face in a crowd also use non-visual clues to help identify people.

The need to know honest information appears to play a role in the development of our non-visual recognition. Autistic people are often very sensitive to deception, even when it’s well intentioned. In many cases we can point to a history of being deceived by people in our lives as a cause, but even those of us who’ve grown up in honest & supportive environments still have a powerful drive towards honesty and candour.

This ties in directly with our emotional needs. Being deceived or not knowing something everybody else seems to know has made us feel awkward, excluded or even completely alien, so there’s an emotional incentive to find ways of identifying people that don’t rely on facial recognition.

The sensory side of non-visual recognition is obviously the biggest aspect of the triad we should be looking at though. It’s only now that I can say for certain that my primary recognition skill is directly tied to my hyper-sensitivity for human sounds. Whether I was born with it our honed it as a survival skill I really don’t know, but I do know that I pick up auditory information most people seem to miss. I’ve got myself in trouble more times than I can mention for overhearing conversations I wasn’t supposed to, or received dirty looks from people who can tell I’m the only one who heard them breaking wind in a crowded room.

There’s more to the way people speak than the sound of their voice or their accent. It’s in the choice and order of the words that they use, in the rhythm and timing, the raising and lowering of pitch when they ask a question, make an impactful statement, or a sarcastic one.

There’s the telltale weight and pattern of their footsteps, their breathing and the little non-speech noises they make. The way they tut, the way they sigh and the little saliva clicks as they open their mouths and a bubble pops. All those are auditory cues that get filed away to make it possible for me to recognise people when their faces are a mystery.

This is why I find it so difficult to recognise anyone in or from a photograph but progressively easier once I see them moving or hear them speak, or walk, or just make mouth noises. If Becky or Bruno in the stories I told last week had called out my name instead of staring at me in shock or waving at me from the other end of a supermarket I’d probably have recognised them instantly, but instead they chose not to and then have a go at me later.

There’s so many clues to a person’s identity that most non-autistic people don’t register, but they’re there all the same. Which ones are most meaningful to someone who’s both face-blind and autistic are highly likely to be related to our sensory profiles. If there’s a sense or a sensory cohort to which we’re more highly attuned, such as my sensitivity to human made sounds, it stands to reason that we’re likely to rely more heavily on that than our other sensory input.

Even visually there are signals outside of faces that can play a huge part in our recognition process.

There’s clothes & accessories, the way people swing their shoulders and hips when they walk, the gestures they use and the way their clothes hang.

Outside of vision and sound there’s a unique smell to everyone that we may not perceive on a conscious level but still helps us to recognise people, a texture to their skin, patterns to their scars and much, much more that can be used to place an individual in our memories.

We all accept that people who are born without a specific sense such as those who are blind, deaf or anosmic naturally learn to perceive and navigate the world using the senses they have and often do things that other people expect to be impossible and the same is true for the highly specific but socially sensitive differences of prosopagnosia.

It’s yet another reason why the efforts of ABA practitioners and even the new “behaviour” policies being discussed in UK schools can have the opposite effect to that intended. They actually hinder our progress and make adult life more difficult than it needs to be. Forcing eye contact in particular, traumatises children into wasting immense energies trying to do something which at best doesn’t provide the feedback they’re told to expect or at worst causes them emotional & physical pain, whilst at the same time holding them back from developing the natural skills they need to succeed in later life.

Next time I’ll continue this short series by looking at some of the questions, comments and stories that have come up about autistic face blindness.

You can watch the video by clicking on any of the images in the body of text.

(c) Autistamatic 2022

![Why I Don't Say "Asperger's" [transcript]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b5a96d_428619c34ce14c21abd05fb94c75bf58~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_551,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/b5a96d_428619c34ce14c21abd05fb94c75bf58~mv2.png)

![Autism Myths - Where Do They Come From? [transcript]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b5a96d_979a827364eb4a37b648272945b44dbf~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_551,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/b5a96d_979a827364eb4a37b648272945b44dbf~mv2.png)

![The BEST Tip For Parents of Autistic Kids [transcript]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b5a96d_284bee433ebc4829a8524d6566c25726~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_551,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/b5a96d_284bee433ebc4829a8524d6566c25726~mv2.png)

Do you often feel like you don't know what you're feeling? Or maybe others say you seem emotionally distant? An alexithymia test can help you explore this specific trait and gain self-awareness.